We are very lucky at Hungerford Arcade to have such a good friend and writer as our brilliant Stuart Miller-Osborne. Stuart has written this remarkable story which I am sure will have you riveted as it did me. Sit down with a nice cup of tea and enjoy.

Rita

Quite

often when you stroll around the Arcade here in Hungerford or, if you

are elsewhere, you will find a book about the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood which was essentially a collection of English painters

and poets and critics which was founded in 1848.

If

you are lucky, you might find a framed print of their work.

you are lucky, you might find a framed print of their work.

The

Thebrotherhood initially consisted of William Holman Hunt (1827-1910),

John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti

(1828-1882).

Its

aim was to reject the approach adopted by the Mannerist

artists.They considered the classical poses and compositions

especially from Raphael to have been a corrupting influence on the

teaching of the day.

aim was to reject the approach adopted by the Mannerist

artists.They considered the classical poses and compositions

especially from Raphael to have been a corrupting influence on the

teaching of the day.

Hence

the title of the group.

the title of the group.

They

drew up a doctrine in the early days which read as follows.

drew up a doctrine in the early days which read as follows.

1/

to have genuine ideas to express

to have genuine ideas to express

2/

to study nature attentively, so as to know how to express them

(nature)

to study nature attentively, so as to know how to express them

(nature)

3/

to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in

previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and

self-parodying and learned by rote

to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in

previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and

self-parodying and learned by rote

4/

most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good picture and

statues

most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good picture and

statues

In

Inshort, it was a freedom of expression with the members being able to

express themselves without borders and by doing so, getting the work

to breathe and be approachable.

If

one looks at works by members (or later members) of the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood then, I personally think that their ideas

are still attractive.

one looks at works by members (or later members) of the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood then, I personally think that their ideas

are still attractive.

Although

one must have something of knowledge of their work, I feel that these

paintings still speak to us today as much as they did some one

hundred and fifty years ago.

one must have something of knowledge of their work, I feel that these

paintings still speak to us today as much as they did some one

hundred and fifty years ago.

But

what of the models. Do we ever consider the models who posed for

these famous works?

what of the models. Do we ever consider the models who posed for

these famous works?

There

are the famous ones such as Lizzie Siddal (1829-1862) who is forever

connected with Rossetti.

are the famous ones such as Lizzie Siddal (1829-1862) who is forever

connected with Rossetti.

But

who was the girl in the centre of the Millais painting, Autumn

Leaves (1856), it certainly was not the tragic Lizzie?

who was the girl in the centre of the Millais painting, Autumn

Leaves (1856), it certainly was not the tragic Lizzie?

I

Ifirst saw this painting in Manchester many years ago and was struck

by the two figures to the left of the painting. Although unable to

help, the gallery assistant did point me in the direction of a book

which revealed that the models were in fact the sisters Alice and

Sophie Gray.

I

made a mental note of this and really forgot about the sisters for

many years until I saw a copy of a painting completed a year later by

Millais called simply, Portrait of a Girl.

made a mental note of this and really forgot about the sisters for

many years until I saw a copy of a painting completed a year later by

Millais called simply, Portrait of a Girl.

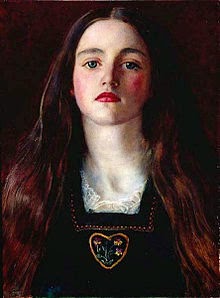

The

artist had used the same model as he had in Autumn Leaves and

after further research, I found this was indeed Sophie Gray

(1843-1882) whose life was equally as tragic as that of Lizzie

Siddel.

artist had used the same model as he had in Autumn Leaves and

after further research, I found this was indeed Sophie Gray

(1843-1882) whose life was equally as tragic as that of Lizzie

Siddel.

What

struck me about the portrait was the sensuality and erotic charge

that this simple painting gave to the viewer.

struck me about the portrait was the sensuality and erotic charge

that this simple painting gave to the viewer.

I

initially thought that the artist might have been the lover of the

sitter, but there is no evidence to suggest that Millais and Sophie

were ever physically involved and also, she was only fourteen when it

was painted.

initially thought that the artist might have been the lover of the

sitter, but there is no evidence to suggest that Millais and Sophie

were ever physically involved and also, she was only fourteen when it

was painted.

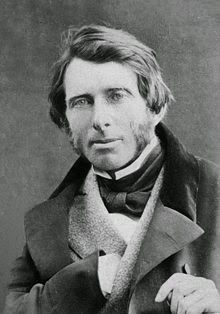

But

this is where my researches became interesting, as did not John

Everett Millais run off with a certain Effie Gray (1828-1897), the

wife of the famed art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) and was Sophie

indeed related to Effie and how long had she known the artist?

this is where my researches became interesting, as did not John

Everett Millais run off with a certain Effie Gray (1828-1897), the

wife of the famed art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) and was Sophie

indeed related to Effie and how long had she known the artist?

My

research was easy, Effie was indeed Sophie’s sister, although some

fifteen years her senior. Sophie had first met Millais in 1853 and he

had completed a rather nice oval watercolour of her in 1854.

research was easy, Effie was indeed Sophie’s sister, although some

fifteen years her senior. Sophie had first met Millais in 1853 and he

had completed a rather nice oval watercolour of her in 1854.

Indeed,

both she and Effie and her sister Alice sat for the artist.

both she and Effie and her sister Alice sat for the artist.

“…What

a delightful little shrewd damsel Sophia is…I do not praise her to

please you, but I think her extremely beautiful, and that she will

even improve, as yet she does not seem to have the slightest idea of

it herself which makes her prettier—I am afraid that ignorance

cannot last long…”

a delightful little shrewd damsel Sophia is…I do not praise her to

please you, but I think her extremely beautiful, and that she will

even improve, as yet she does not seem to have the slightest idea of

it herself which makes her prettier—I am afraid that ignorance

cannot last long…”

Indeed,

when he painted Sophie in 1857, she was as I have noted, only

fourteen but the charge of the painting hints at a much older model.

The sitter of this unusual work looks as she has attained early

adulthood.

when he painted Sophie in 1857, she was as I have noted, only

fourteen but the charge of the painting hints at a much older model.

The sitter of this unusual work looks as she has attained early

adulthood.

Sophie

occupies a large part of the canvas and is lit in a delicate fashion

from the left which highlights her golden brown hair and hints at its

auburn highlights. Her clothes are not memorable and are simply

decorated with an embroidered heart containing three flowers within.

occupies a large part of the canvas and is lit in a delicate fashion

from the left which highlights her golden brown hair and hints at its

auburn highlights. Her clothes are not memorable and are simply

decorated with an embroidered heart containing three flowers within.

I

have often thought that this simple embroidery contained a secret

message and to some extent, my enquiries continue. I believe that the

artist left a quiet message in the decoration.

have often thought that this simple embroidery contained a secret

message and to some extent, my enquiries continue. I believe that the

artist left a quiet message in the decoration.

Maybe

it is a declaration of his attraction or love for the sitter or, it

might be my own fancy and it is a simple decoration and like others I

am reading too much into it.

it is a declaration of his attraction or love for the sitter or, it

might be my own fancy and it is a simple decoration and like others I

am reading too much into it.

Sophie’s

long hair frames the portrait and mingles with the dark background.

There is a sniff of lace at her throat and her pale face contrasts

with the darker colours used.

long hair frames the portrait and mingles with the dark background.

There is a sniff of lace at her throat and her pale face contrasts

with the darker colours used.

She

stares at the viewer with her cold blue eyes which are expressionless

to the extreme. There is no clue as to what she was thinking or maybe

she is challenging the viewer to probe her thoughts (or, this might

have been Millais and Sophie’s jest who knows)?

stares at the viewer with her cold blue eyes which are expressionless

to the extreme. There is no clue as to what she was thinking or maybe

she is challenging the viewer to probe her thoughts (or, this might

have been Millais and Sophie’s jest who knows)?

Her

lips and rosy cheeks again contrast the darkness and the light of the

painting. Her lips are ruby red and are pursed in defiance and her

rosy cheeks hint at fluster. These are all enigmatic clues which

suggest things unseen.

lips and rosy cheeks again contrast the darkness and the light of the

painting. Her lips are ruby red and are pursed in defiance and her

rosy cheeks hint at fluster. These are all enigmatic clues which

suggest things unseen.

Sophie’s

chin is defiantly but subtly tilted, hinting at self-confidence

(which might again be a jest).

chin is defiantly but subtly tilted, hinting at self-confidence

(which might again be a jest).

It

is obvious that there was a connection between Millais and Sophie as

the artist has produced a very haunting portrait which celebrates the

beauty of the sitter and the fondness that he had for her.

is obvious that there was a connection between Millais and Sophie as

the artist has produced a very haunting portrait which celebrates the

beauty of the sitter and the fondness that he had for her.

One

Onehas only to look at his paintings of the other Gray sister’s. These

are excellent works in their own right but they are just portraits.

There is no connection between the sitter and the artist and

certainly no erotic charge.

It

is well known that Millais ran off with Effie Gray and many stories

were created at the time especially the one about Ruskin’s horror

at the sight of his wife’s pubic hair.

is well known that Millais ran off with Effie Gray and many stories

were created at the time especially the one about Ruskin’s horror

at the sight of his wife’s pubic hair.

It

was really a case of two people in a marriage not hitting it off and

drifting apart.

was really a case of two people in a marriage not hitting it off and

drifting apart.

Victorian

society was easily shocked at abandonment especially if the wife

eloped with her lover, so stories were made up to cover some of

Ruskin’s peculiarities.

society was easily shocked at abandonment especially if the wife

eloped with her lover, so stories were made up to cover some of

Ruskin’s peculiarities.

Effie

was the scarlet woman who had run off with an artist,

although Millais was quite a respectable one.

was the scarlet woman who had run off with an artist,

although Millais was quite a respectable one.

On

researching this, I found out that Sophie actually helped her sister

to elope by train (Effie travelled to Scotland whereas Sophie

alighted at Hitchin where she met her father as they were to deliver

a package on to their solicitors who would forward it on to Ruskin

noting his wife’s actions).

researching this, I found out that Sophie actually helped her sister

to elope by train (Effie travelled to Scotland whereas Sophie

alighted at Hitchin where she met her father as they were to deliver

a package on to their solicitors who would forward it on to Ruskin

noting his wife’s actions).

This

package included her wedding ring and the keys to the house.

package included her wedding ring and the keys to the house.

Indeed

Ruskin came across as being a rather nice fellow who I believe,

understood in time why Effie ran off with Millais.

Ruskin came across as being a rather nice fellow who I believe,

understood in time why Effie ran off with Millais.

Others

may disagree with my thoughts, but there are always two or three ways

to look at everything.

may disagree with my thoughts, but there are always two or three ways

to look at everything.

I

personally think that if Millais had not met Effie, then he would have

married Sophie and the story that I am about to tell might not have

had such a tragic ending.

personally think that if Millais had not met Effie, then he would have

married Sophie and the story that I am about to tell might not have

had such a tragic ending.

Sophie

sadly had always been highly strung and was further damaged when she

acted as a go-between between Ruskin and Effie.

sadly had always been highly strung and was further damaged when she

acted as a go-between between Ruskin and Effie.

She

was also indulged by Ruskin’s domineering mother in an attempt to

turn her against her sister. But being loyal she kept her sister

informed of everything that was said.

was also indulged by Ruskin’s domineering mother in an attempt to

turn her against her sister. But being loyal she kept her sister

informed of everything that was said.

Sophie

began to exhibit major mental health problems in her mid-twenties and

was, in 1868 sent away from her home to stay in Chiswick under the

care of a certain Doctor Thomas Tuke who specialised in mental

health.

began to exhibit major mental health problems in her mid-twenties and

was, in 1868 sent away from her home to stay in Chiswick under the

care of a certain Doctor Thomas Tuke who specialised in mental

health.

Sadly,

conditions such as Sophie’s were often diagnosed as hysteria which

was thought to be quite common in young women.

conditions such as Sophie’s were often diagnosed as hysteria which

was thought to be quite common in young women.

What

is known, is that Sophie suffered from Anorexia Nervosa which

contributed to her overall condition.

is known, is that Sophie suffered from Anorexia Nervosa which

contributed to her overall condition.

.

In

1873 she married (unhappily it turned out), to a Scottish Jute

manufacturer James Key Caird.

1873 she married (unhappily it turned out), to a Scottish Jute

manufacturer James Key Caird.

He

Hewas wealthy but neglected Sophie when she needed him most. They had a

child Beatrix Ada (who was later painted by Rossetti) and she lived

mostly alone with her daughter in Dundee and Paris.

As

with patient’s suffering from this condition, she lost weight

rapidly and her health deteriorated and she was again committed to

the care of Doctor Tuke, but she never really recovered and passed

away on the 15th of March 1882.

with patient’s suffering from this condition, she lost weight

rapidly and her health deteriorated and she was again committed to

the care of Doctor Tuke, but she never really recovered and passed

away on the 15th of March 1882.

Her

cause of death was recorded mysteriously as exhaustion and

atrophy of the nervous system.

cause of death was recorded mysteriously as exhaustion and

atrophy of the nervous system.

There

were rumours of suicide but these were never really followed up.

were rumours of suicide but these were never really followed up.

I

would like to think that given the right circumstances, Sophie might

have been able to conquer or at least live with her demons and a late

portrait by Millais painted in 1880, shows a much different Sophie.

would like to think that given the right circumstances, Sophie might

have been able to conquer or at least live with her demons and a late

portrait by Millais painted in 1880, shows a much different Sophie.

She

has aged and looks older than her thirty-seven years. Her once

luxurious hair is showing evidence of greyness and is tightly wound.

has aged and looks older than her thirty-seven years. Her once

luxurious hair is showing evidence of greyness and is tightly wound.

Sophie’s

posture is nervous almost insular and she bends her fingers with

nervous impression. She is dressed modestly and could almost be a

spinster hidden away in the shadows.

posture is nervous almost insular and she bends her fingers with

nervous impression. She is dressed modestly and could almost be a

spinster hidden away in the shadows.

Her

colours are sombre and Millais has almost created a ghost like figure

in complete contrast with the sensuous portrait painted some

twenty-three years previously.

colours are sombre and Millais has almost created a ghost like figure

in complete contrast with the sensuous portrait painted some

twenty-three years previously.

It

is one of the most tragic of his works and in my view, should be hung

next to the 1857 portrait but this unlikely to happen.

is one of the most tragic of his works and in my view, should be hung

next to the 1857 portrait but this unlikely to happen.

Other

interesting facts I found whilst researching this article was that

sadly, Sophie’s daughter died in 1888 at exactly the same age as

her mother had been when she sat for the famous portrait. .

interesting facts I found whilst researching this article was that

sadly, Sophie’s daughter died in 1888 at exactly the same age as

her mother had been when she sat for the famous portrait. .

Her

husband, although neglectful of Sophie, helped to fund Ernest

Shackleton’s Trans-Antarctic expedition (1914-1917) and was a major

benefactor to the city of Dundee.

husband, although neglectful of Sophie, helped to fund Ernest

Shackleton’s Trans-Antarctic expedition (1914-1917) and was a major

benefactor to the city of Dundee.

Although

he has been painted as being neglectful of Sophie, the death of his

wife and his daughter within six years of each other seemed to have

hit James Caird hard and he became increasingly philanthropic in his

later years (he died in 1916).

he has been painted as being neglectful of Sophie, the death of his

wife and his daughter within six years of each other seemed to have

hit James Caird hard and he became increasingly philanthropic in his

later years (he died in 1916).

He

contributed £18,500 to the Dundee Royal Infirmary so that they could

erect a hospital for the treatment of cancer. This was one of his

many generous gifts to the city.

contributed £18,500 to the Dundee Royal Infirmary so that they could

erect a hospital for the treatment of cancer. This was one of his

many generous gifts to the city.

I

believe that James was just a typical Victorian businessman but in

Sophie’s case, his neglect was not helpful. Maybe he did not fully

understand Sophie’s condition and the dangers it presented.

believe that James was just a typical Victorian businessman but in

Sophie’s case, his neglect was not helpful. Maybe he did not fully

understand Sophie’s condition and the dangers it presented.

If

I had the funds available (and if the present owners would sell), I

would purchase Sophie’s 1857 portrait and loan it to a gallery so

that visitors could examine this astonishing work and maybe try to

discover some of its secrets.

I had the funds available (and if the present owners would sell), I

would purchase Sophie’s 1857 portrait and loan it to a gallery so

that visitors could examine this astonishing work and maybe try to

discover some of its secrets.

It

is one of the most enigmatic of paintings.

is one of the most enigmatic of paintings.

Stuart Miller-Osborne

For all the latest news, go to our Newsletter at www.hungerfordarcade.co.uk