It’s 1942. You’re a fighter pilot with RAF Coastal Command. You’ve been forced to ditch your plane into the Atlantic Ocean and you’ve managed to scramble into your life raft. But far from land and all alone, you have no way to call for help… Or do you?

This bright yellow steel tube contains the answer.

This is an emergency kite designed to be used alongside the AN/CRT 3 or “Gibson Girl” Transmitter. In 1941 the US captured a German designed portable transmitter. Hand cranked and connected to a box kite for an aerial, this ingenious contraption could be used to send a distress signal from anywhere in the world, with no other power source necessary.

|

| The uniquely shaped transmitter. |

The Americans took this design and improved upon it to come up with the Gibson Girl. Affectionately named for it’s curious shape it was named after the slim waisted young ladies as depicted by Charles Dana Gibson, a famous artist and fashion illustrator of the late 19th Century.

|

| A typical Gibson Girl. |

The shape was intended to enable the user to steadily hold the device between his legs while operating the crank handle.

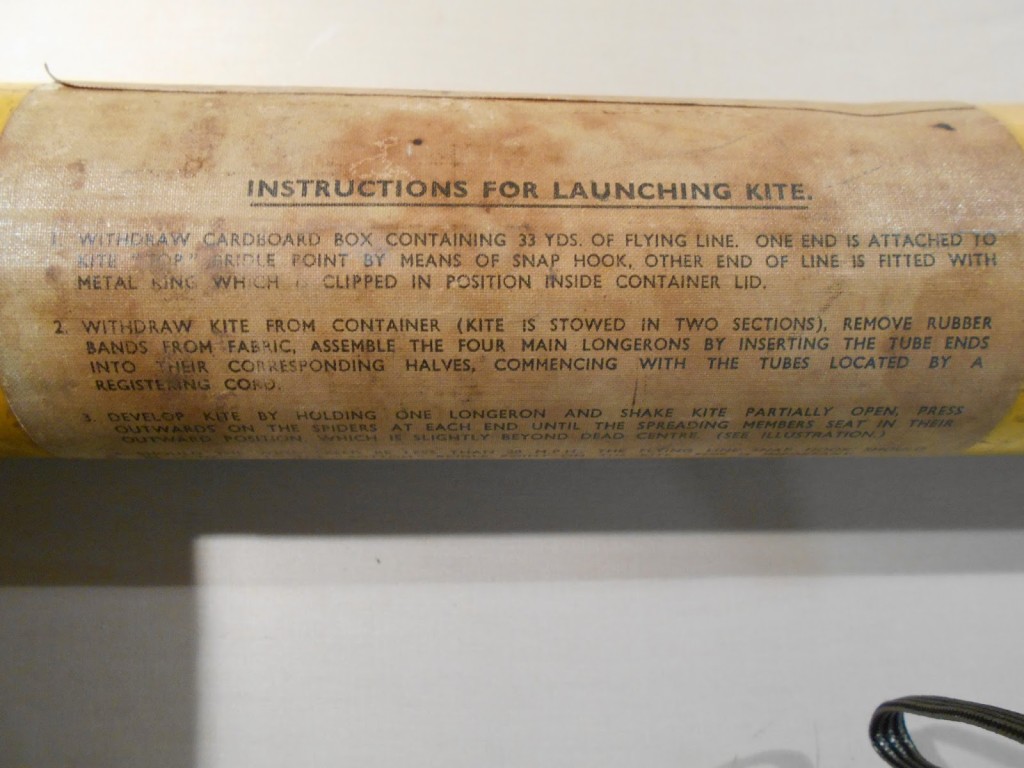

According to the instructions on the side of the container, the kite is easy to construct, with only six easy steps to put it up. Unfortunately the frame of the kite is all that remains inside this particular container. The canvas is completely missing, as is the line and the transmitter – although that would never have been carried inside the tube anyway.

Assuming you managed to get yourself stranded on a windy day and had accomplished the challenge of construction, all that remained was to feed the line out to it’s maximum height, hold the transmitter between your legs and crank the handle. As you will read in the real-life report below, cranking could be a very arduous task.

The transmission, which could be picked up 200 miles away, was an automatic SOS or alternatively hand keyed Morse if you had a specific message to transmit. This signal could then be homed in on by the rescue aircraft radio compass.

|

| The assembled kite and original container |

Today, the technology is obviously long redundant. Satellite phones, GPS trackers and all sorts of other things I don’t understand are clearly far more practical than this historical piece of equipment. However, the legend of the kite lives on! Sometimes very cheap to pick up at car boot sales (or antiques centres!) it was simply a very well designed box kite. Kite flying enthusiasts to this day swear that this is the best kite they have ever flown. So if you happen to pick one up somewhere, make sure you bring it down to the Arcade and we can take it up onto the common and see how it flies!

Alex

Below is a report from the 39th Bombardment Group flying for the US Airforce in which the Gibson Girl is mentioned. NB: Please be aware that this report contains details of actual events and if you are likely to be affected by mentions of plane crashes, read on at your own risk. Nobody in the following report was hurt during the events.

Report by S/Sgt James Schwoegler, Radio

Operator 39th Bomb Group (VH) Crew 30.

The plane made it out over the ocean, but

then the third engine’s propeller broke off,

slicing the plane’s fuselage from the middle

to the top and cutting the control the plane’s

fourth engine.

They had only one working

engine left.

The pilot made the decision for the crew to

bail out, and it was Schwoegler’s job to radio

in their location.

They planned to ditch near

a location code named “Lot’s Wife,” which

was actually named Sofugan, described by

Schwoegler as “a rock sticking out of the

ocean.”

The crew began to jump out of the airplane

through a hatch leading to the landing wheel

well in the nose. The problem for Schwoegler

was that lifting the door to the wheel well

blocked him in the radio area. After the rest

of the crew had jumped out, Schwoegler

closed the hatch door so he could get

through, much to the pilot’s surprise. “The

pilot said ‘Jim, get the hell out!'”

Schwoegler managed to swim to the surface

where he attempted to inflate a lifeboat that

was part of his gear. “I pulled it open and

nothing.,” he said. Fortunately he was able

to manipulate the CO2 cartridge that inflated

his raft and get it to work.

The plane’s crew

was spread over a broad area, but thanks to

Schwoegler’s signal a B-17 rescue plane was

able to locate the crew and drop them a Higgins

lifeboat with food and medical supplies.

Safe in the lifeboat, the ordeal of the 10 survivors

was not over. “The morning brought

so much fog, you couldn’t see from here to

the next house,” Schwoegler explained. This

hampered rescue efforts and forced the crew

to use a “Gibson Girl,” a shapely radio designed

to be held between the legs and operated

with a crank. When cranked, the radio

sent out a constant S.O.S. To send the signal,

an antenna was raised on a kite. As the

radioman, the job of cranking fell to

Schwoegler. “I don’t know how long I

cranked,” he said. “I was real disappointed

no one volunteered to take it except the

navigator.” His efforts bore fruit in the form

of a submarine. “Is it Japanese or American?”

Schwoegler wondered. “Then I saw a

guy with a flaming red beard and I knew it

was an American. It was the best sight I

ever saw.”

He still has the kite antenna that led the rescuers

to them, but he accidentally left

the “Gibson Girl” on the first sub when they

transferred. “The (sub crew) loved having

us,” Schwoegler recalled. “They gave up

their bunks and everything. The first night

(aboard) we ate chicken and steak. We hadn’t

eaten like that in a while.”