Hungerford Arcade’s wonderful friend and author, Stuart Miller-Osborne has written this amazing article on Samplers. It is a subject that has always fascinated me and the fact that lighting was so primitive in those days but the girls/women could sew so beautifully.

The Mystery of Samplers

Although I do not own a sampler I have always been fascinated by them as in my view, they open a window quite easily into the past.

Before writing this short piece, I explored the various antique outlets in Hungerford to see how many I could find.

Before writing this short piece, I explored the various antique outlets in Hungerford to see how many I could find.

In the short week of my review, I found some fascinating examples many of which I would have liked to have purchased.

But on the whole, they were out of my determined price range as their cost approached three figures.

Do not let this put you off, as if you purchase a sampler then you will have an item with a unique history hanging from your wall.

Although they seemed to be purely decorative, samplers actually had a function and this was the reason for their genesis over six hundred years ago.

As most of us are aware, the first book was not published in England until 1477 when William Caxton and his Westminster press made an appearance.

But supposing fifty years previously you as a needlewoman were required to follow a pattern, then you had a problem.

You could not nip down to the local library and pick up a book on the subject.

But an answer was to hand, basically a narrow piece of cloth which was used to record the pattern required.

They were logically called samplers (from the French essamplaire which roughly means a work copied).

In short, you were given (or maybe they were passed down in families) a pattern to follow and you progressed from there.

As books became more popular, it was not that long before the first pattern book was published (in Augsburg in 1523).

Others followed and by 1600 the sampler in its initial function was more or less redundant.

Others followed and by 1600 the sampler in its initial function was more or less redundant.

Books had had the impact that the internet has had on our everyday lives today.

But although without a job our friend the sampler was not gone and forgotten.

They retained a use for teaching girls the various sewing techniques which would help them in later life.

There were items such as darning samplers and sewing samplers which, as their name implies, were useful when making clothes or just committing repairs to others.

Earlier samplers were nothing like the ones we see in frames today. They were for the most part long and narrow (rather like a margin on an essay) and to some extent, were used for this purpose.

They were working items and it was not until the eighteenth century that samplers began to change their shape.

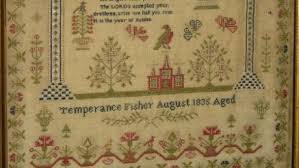

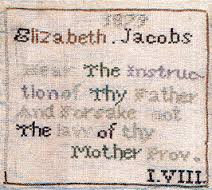

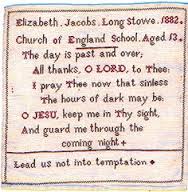

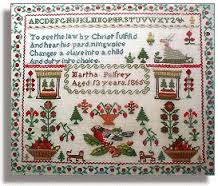

They ceased to be long and narrow and became square. Their content was changing as well. Samplers were often used to record events (whether they be good or bad) within families and quite often celebrated God.

When visiting the V&A (which has a fantastic collection of samplers) I have found slightly later ones which contain moral verses and the like.

Poems began to appear and representations of birds and trees and houses to name but a few were to be found.

Celebrations of the monarchy and letters of the alphabet were also seen, the latter having a practical use as many people were quite illiterate.

Obviously, techniques changed and to some extent the quality of the materials used, but overall samplers stayed the same.

For some reason, nineteenth century samplers continue to attract my interest, although I have a great admiration for earlier samplers which I have seen in various museums in the UK.

I think my interest stems from the social history of the items. A great number of samplers made in the nineteenth century were executed by younger women as part of their education.

One has only to visit the Hungerford Arcade to see how exquisite these items are. The dexterity in the fingers of these young ladies is astonishing to say the least.

The hours and days they must have spent on their samplers do not warrant calculation.

This is the attraction of samplers to me and I believe this attraction is shared by many others as samplers do not seem to remain in the Arcade for very long.

The Victorian samplers also act as family diaries recording (as I have previously noted) births, deaths and marriages.

They remind me of Victorian family Bibles which quite often retain these records.

Some are incredibly sad, a living record of their creation.

In a reference book I am reading, the author mentions a Martha Grant who appears to have started a sampler at the age of ten in 1833. This date is enclosed in a cartouche on the left hand side of the work.

In a reference book I am reading, the author mentions a Martha Grant who appears to have started a sampler at the age of ten in 1833. This date is enclosed in a cartouche on the left hand side of the work.

But opposite there is a second cartouche which records her date of death which was on the 31st of October 1834.

Obviously, she could not have added the latter detail and one wonders whether Martha actually started the sampler as the technique is constant throughout.

Maybe the sampler was created by her sister or her mother in memory of Martha, this is hard to determine..

It is a mystery of time which will not be resolved.

At the time of writing (July 2015), there are a couple of lovely Victorian samplers in the Arcade that you can admire even if you do not purchase them. If my memory serves me correctly, one of them dates from 1821 and although not as tragic as Martha’s sampler, it is incredibly interesting and one feels that they are looking at life nearly two hundred years ago.

Queen Victoria would have only been two and the poets Shelley and Byron would have been at the height of their powers.

Poor Keats would have been in Italy in search of a respite in his terrible disease.

But somewhere in the United Kingdom, a young lady ( I cannot remember her name) would have been working on a sampler maybe as an education or maybe for her complete pleasure.

Little would she have known that her delicate work would be for sale in our small West Berkshire town in 2015.

As with Martha, this young craftswoman has faded into history leaving very few clues.

That is the fascination for me, the obscurity of time. Each time I see a Victorian sampler I think of its creator and admire the beauty of their work.

This said, some samplers from the period are charmingly eccentric in their presentation. You often find capital letters in the middle of words and very occasionally misspellings. I saw a lovely one in Dorchester about twenty years ago where there were a large number of spelling mistakes in a simple prayer (God grace, His keapimg etc etc).

I am sure that young Emma Simpson (I remember her name clearly to this day) was either dyslexic or was just rather bad at spelling or was doing the sampler as a punishment and was totally disinterested.

The overall presentation was charmingly chaotic and I wish that I had purchased the sampler at the time.

But I was on my way to Weymouth Sands and to have had a sampler plus two children in tow would have not been practical.

It was also raining at times that day and we spend a number of hours in nearby Preston drinking endless cups of tea.

I should have taken the plunge as the dealer was asking a very fair price for the item.

I will buy a Victorian sampler one day.

I will find the right one which attracts me instantly and I will behave foolishly with my wallet. But not for now.

Price wise, as I have already noted, you can expect to pay a good price for a Victorian sampler (I have not seen any created before 1800 for sale for many years).

If you budget around one hundred pounds then I think you will find an acceptable example to purchase. This said, you can pay a lot less or a lot more.

The cheapest sampler that I have seen recently was one that was created in 1927 which was a bargain at twelve pounds.

It was not as ornamental as the Victorian samplers but was a fine work.

In Henley recently, I found a rather crudely worked sampler dating from 1864 for sale for twenty-eight pounds which was good value.

It is a matter of searching around.

When you find the sampler that really attracts, you will buy it even if it is a little out of your range.

If I was successful with my lottery ambitions then I would start a museum for samplers for future generations to enjoy, from Miss Simpson’s mischief to the most exquisite Victorian workings.

I think this would be fun and would inspire people to pursue this art which still has a following but in my view is a little under the radar at present.

But I may be wrong and happily so.

Stuart Miller-Osborne