We all remember the nursery rhyme from our childhood which begins with the words London Bridge is Falling Down. Well the London Bridge that I am going to share with you

did not fall down but was transported stone by stone to a lake in Arizona just over fifty years ago. But why am I interested in a bridge which although in America, has a place in the memories of all Londoners over the age of fifty?

By John L.Stoddard (died 1931), Scan by Robert Schediwy [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The answer is easy as I am the proud owner of a small piece of the nineteenth century bridge which I purchased today from the Arcade.

I had not really planned to visit the Arcade, but my daughter wanted to pop in to browse around (she lives in Kent and is an infrequent Hungerford visitor). After I had completed the grandchildren watch, I was left alone as the little wonders made their way to the canal to feed the ducks with their mum. I was free once more and decided to visit the book section for some peace and quiet. It was as I turned towards the stairs that I noticed what seemed at first to be a small lump of rock on a small shelf to my right. Initially I ignored it as I thought that there might be an Eliot first hidden away awaiting my discovery. But as I rummaged through the books, I thought of the lonely piece of rock sitting on its own at the base of the stairs.

I selected a modern book on Uxbridge, (which is where I met Caron whilst at college) and a 1910 London guide book. When I examined the rock, which I instantly identified as a piece of granite, I soon became aware of its unique historical significance. It was an original piece of Rennie’s 1831 London Bridge which spanned the mighty River Thames for over one hundred and thirty years. I decided to purchase it on the spot and write a short article about this famous lost bridge.

The identification of the stone was the easy part, but how did I know that it was from Rennie’s bridge? The answer was simple as there was a small plaque on the mounting noting this fact. But what of London Bridge? Well as most of us are aware, there have been a number of bridges that have been called by that name. The first one was built by our friends the Romans (what did the Romans ever do for us?) and was not much more than a glorified pontoon. But as times matured, our Italian friends replaced this temporary bridge with a permanent piled bridge which was maintained and protected by a small garrison nearby.

After the Romans returned to Italy in the 5th century, London was slowly abandoned and the bridge suffered as a result. It is thought that the bridge was rebuilt by either Alfred the Great or later on by Etheired the Unready in or around 990. However, history does record that William the First did rebuild the bridge and that it was repaired during the reign of William the Second. The bridge was further maintained (or maybe rebuilt) during the reigns of both Stephen and Henry the Second. It was Henry who created a monastic guild (The Brethren of the Bridge) to oversee all aspects of the crossing. A man known by the lovely name of Peter of Colechurch was the warden of the bridge and oversaw its last rebuilding in timber in 1163.

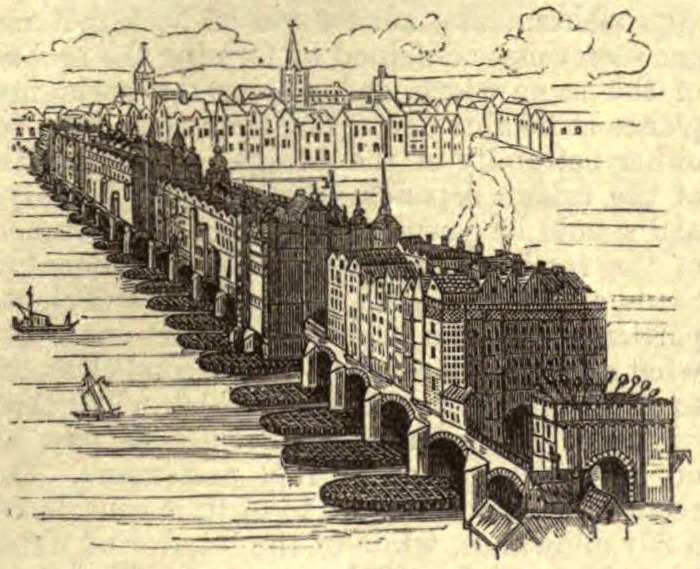

And now we come to the next bridge and, which in its way, is more famous than all the others. Old London Bridge which crossed the Thames between 1209 and 1831 was, in its way, the result of a very bloody murder. The penitent King Henry the Second after he foolishly ordered the assassination of the popular Thomas Becket in 1170, commissioned the building of a new stone London Bridge. Although I am sorry for his unforgivable act, I believe that Henry was quite smart politically and knew that a shiny new bridge would help to integrate his name with his people once more. And what a bridge it was.

Work began in 1176 and was supervised by our old friend Peter of Colechurch. Unlike today where mega engineering works are almost put up in days, the building of the new bridge took over thirty three years and was finished in 1209 during the reign of King John. In common with today’s projects, the costs of building the bridge were astronomical (as was recently demonstrated by the ill-fated and ill thought out Garden Bridge over the Thames). John tried to cover the costs by licencing out commercial and domestic plots on the bridge (This I believe, was the genesis of the famous song).

However, bridges are expensive and this was never going to cover the costs and in 1284 in exchange for loans to King Edward the First, the City of London acquired the charter for the maintenance of London Bridge which included all duties and tolls. The new bridge was pretty impressive being some nine hundred feet long and supported by nineteen arches.

It also had a drawbridge to allow for the passage of taller ships and because times demanded it, had defensive gatehouses at each end. What I did find amusing was my discovery that the bridge had a multi-seated public latrine overhanging the parapets (I would imagine that sailing under the bridge in those days was quite an experience). The latrines must have been popular as between 1382 and 1383 a new one was constructed at the north end of the bridge (I wonder if there was a small toll for this and this is where the term “Spend a Penny” originated). But enough of this toilet humour, grow up Stuart you are not at school now!

As I noted earlier, to try to recoup some of the costs, buildings were allowed on the bridge and as normal this got out of hand quite quickly. It was an obvious fire hazard and added to the load that the arches of the bridge supported.

In 1212 there was a very serious fire on the bridge which occurred at both ends (trapping the poor people in the middle). History does not record whether this was deliberate or not, but the burning of both domestic and commercial properties during Wat Tyler’s Peasants Revolt of 1381 and during the Jack Cade Rebellion of 1450 were deliberate. Strangely enough, the damage caused by the major fire on the bridge on 1633 acted as a firebreak during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Going back a hundred or so years, by Tudor times there were some two hundred buildings on the bridge and some were up to seven storeys high and still, buildings were added such as the palatial Nonesuch House in 1577.

There was immense congestion with traffic coming in both directions and to add to the fun, I am told that the less secure structures sometimes fell into the Thames (hence the song).

On a slightly more fun note, the bridge was also used to display the severed heads of traitors impaled on spikes (after being dipped in tar and boiled to preserve them against the London weather).

William Wallace was the first to appear followed in no particular order by Jack Cade, Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell and many others. A German visitor once remarked that he counted over thirty heads on the bridge. The practise was supposed to have ceased in 1660 when Good King Charles came to the throne but was reported as late as 1772. Today, if the practice was still in operation, I can think of a few candidates for the honour but will leave my humour there (all suggestions on a plain white envelope please).

During the rationalisation of the bridge (1758-1762) all the houses and shops were demolished (that is if they had not fallen in already) and to improve navigation, the central arches were modernised. But the bridge was past its working life and was dying on its feet.

In 1799 a competion was held to design a replacement for the old medieval bridge.

Thomas Telford threw his hat into the ring amongst others, but a design by John Rennie won the competition and in 1824 work commenced. As the new bridge was situated some one hundred feet away from the old one, the medieval bridge continued to be used until the new bridge was completed in 1831. The old bridge was then demolished without ceremony.

The new London Bridge cost an amazing £2.5 million pounds to complete which taken at today’s costs, would be some £208 million. This bridge was some 928 feet long and was constructed out of Haytor granite. It was opened by King William the Forth and Queen Adelaide on the 1st of August 1831 with great celebration. It proved very popular and by 1896 was the busiest point in London with some 8000 pedestrians and 900 vehicles using it every day. Due to this congestion, it was later widened by thirteen feet using granite corbels but there was a problem. The bridge was sinking.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6a/David_Cox_-_The_Opening_of_the_New_London_Bridge_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons English artist. painted in 1831

By 1924 the east side had sunk by some four inches and this was not going to stop as it was sinking at a rate of about an inch every eight to ten years. It was decided that the bridge would have to be replaced and in 1967 the bridge was put on the market. A council member had suggested selling the bridge, although the idea initially seemed a little odd. But as with all crazy ideas there was an element of foundation and here is where the strange story begins.

On the 18th of April 1968 London Bridge was sold to an American entrepreneur Robert P McCulloch. His idea was that the bridge be taken apart with each part carefully numbered and shipped via the Panama Canal to California and then on to Lake Havasu City in Arizona. It was to span the Bridgewater Channel and act obviously as a bridge but also as a tourist attraction. It was a hare-brained idea but it worked against all odds and can be found in its new location to this day after being rededicated in October 1971.

I can hear a question from the audience. If the bridge was taken down stone by stone how is it possible that you have a piece of the granite from this bridge not far from where you are writing this article? This confused me at first, but I soon found the answer as some of the stones from the bridge did not make it to sunny Arizona and were left behind at the Merrivale Quarry in Princetown in Devon. This quarry was abandoned in 2003 due to flooding and the remaining stones were sold in an online auction. That is where my block of granite came from and although I have studied photographs of the 1831, bridge I have no clue to its location, although the weathering indicates that it was exposed, But then again, Princetown is not exactly Arizona so I can only guess as to its location on the Rennie bridge.

If I have whetted your appetite with regard to Rennie’s bridge there is no need to travel to Arizona to see an example of his work as between Bradford on Avon and Bath there is a magnificent aqueduct which I have visited on many occasions. If you travel along the railway between Bath and Bradford or in the opposite direction, then you will pass under it. Although it is crumbling a little it is a magnificent sight and can be crossed on foot or along the Kennet and Avon Canal.

Dundas Aqueduct

The new bridge which was opened in 1973, is a familiar sight and most of us have crossed in on numerous occasions. The structure comprises of three spans of pre-stressed concrete box girders and is 928 feet long and it was built to last. It later survived a collision with HMS Jupiter in 1984 which caused damage to both ship and bridge.

The new London Bridge also featured in the 2002 movie, About a Boy starring Hugh Grant. Whilst the 1831 bridge was noted in The Wasteland by TS Eliot in which he compares the faceless London commuters to the hell-bound souls in Dante’s Divine Comedy. I am off to Margate next week to see an exhibition on Eliot’s famous work and wonder if London Bridge will be featured.

You can find most things at most times in the Arcade, but I was rather surprised when I found that small piece of granite late of London Bridge and I have retired it to one of my shelves as I think that after all these years it needs a rest.

Who knows, you might find another piece of the bridge when you visit the Arcade as London buses always come in pairs so why not London bridges.

Good luck in your future searches and perhaps, if you brave the Devon mists, you might find a few pieces of the bridge in the Princetown quarry.

Sadly, our most recent memory of London Bridge was the ghastly terrorist attack in June 2017 in which eight poor people were killed either on the bridge or in the nearby Borough Market area. I dedicate this short article to those who died or were injured on that dreadful day.

Stuart Miller-Osborne